Three weeks ago, Daron Acemoglu gave a talk on Markus Brunnermeier’s “Markus Academy” on YouTube on the Acemoglu-Johnson book “Power and Progress”, about which I wrote a short post in May. I watched this talk today and I heartily endorse it both as a lively and short summary of the book and for the good questions Brunnermeier asked. I liked it enough to immediately add it to my Economic Inequality course syllabus for the fall. You can watch it here: https://youtu.be/eGqaOhTq060

Category: Inequality

Income Inequality and COVID-19

It has been a very long time since I last made a post here. I am coming back with a post about the relationship between income inequality and COVID-19.

The latest issue of The Economist has an article on this topic, which led me to three recent studies about this relationship and an interesting Twitter thread. (Do watch out for the careless conflation of wealth with income in the second tweet in the thread.) I will say a few words for each of the three studies. Before I do that, I need to issue the disclaimer that I am not a statistician or an econometrician, therefore I cannot, and will not, claim to evaluate the appropriateness of the statistical modeling in these studies.

Let’s start with “Association Between Income Inequality and County-Level COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in the US”, by Annabel X. Tan, MPH; Jessica A. Hinman, MS; Hoda S. Abdel Magid, PhD; Lorene M. Nelson, PhD, MS; Michelle C. Odden, PhD, from JAMA Network Open, doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.8799. The authors collected data on COVID cases and deaths for a year (2020-03-01 to 2021-02-28), as well income inequality (measured by the Gini coefficient) for 3220 counties in all 50 states plus Puerto Rico and DC. Their main finding was a positive correlation between income inequality and COVID cases and deaths, which was most pronounced in the summer of 2020. Several additional variables were included as controls, such as the poverty rate, age, race, mask use, crowding, educational level, urban versus rural population share, and availability of physicians. I find it remarkable that income inequality showed up as correlated with COVID cases and deaths in the presence of all these additional variables that one would expect to be more strongly correlated with COVID outcomes.

Next, we’ll talk about “COVID‐19 and income inequality in OECD countries” by John Wildman, The European Journal of Health Economics (2021) 22:455–462 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-021-01266-4. The COVID variables are cumulative deaths per million and recorded daily cases per million in the early months of the pandemic. In the words of the author, “The results demonstrate a significant positive association between income inequality and COVID-19 cases and death per million in all estimated models. A 1% increase in the Gini coefficient is associated with an approximately 4% increase in cases per-million and an approximately 5% increase in deaths per-million.” The author proposes that income inequality is a proxy for other variables that correlate with bad COVID outcomes, such as “poor housing, smoking, obesity and pollution.”

Finally, let’s take a look at “The trouble with trust: Time-series analysis of social capital, income inequality, and COVID-19 deaths in 84 countries” by Frank J. Elgar, Anna Stefaniak, and Michael J.A. Wohl, Social Science & Medicine 263 (2020) 113365. Here is the abstract of the paper:

Can social contextual factors explain international differences in the spread of COVID-19? It is widely assumed that social cohesion, public confidence in government sources of health information and general concern for the welfare of others support health advisories during a pandemic and save lives. We tested this assumption through a time-series analysis of cross-national differences in COVID-19 mortality during an early phase of the pandemic. Country data on income inequality and four dimensions of social capital (trust, group affiliations, civic re- sponsibility and confidence in public institutions) were linked to data on COVID-19 deaths in 84 countries. Associations with deaths were examined using Poisson regression with population-averaged estimators. During a 30-day period after recording their tenth death, mortality was positively related to income inequality, trust and group affiliations and negatively related to social capital from civic engagement and confidence in state in- stitutions. These associations held in bivariate and mutually controlled regression models with controls for population size, age and wealth. The results indicate that societies that are more economically unequal and lack capacity in some dimensions of social capital experienced more COVID-19 deaths. Social trust and belonging to groups were associated with more deaths, possibly due to behavioural contagion and incongruence with physical distancing policy. Some countries require a more robust public health response to contain the spread and impact of COVID-19 due to economic and social divisions within them.

I find these papers extremely interesting, and I want to make them part of my economic inequality course. You could say that this post is my very rough first reaction, simply noting the main conclusions of this research, conclusions that point out a clear connection between income inequality and the COVID-19 pandemic outcomes.

BPEA conference on COVID-19 and the economy

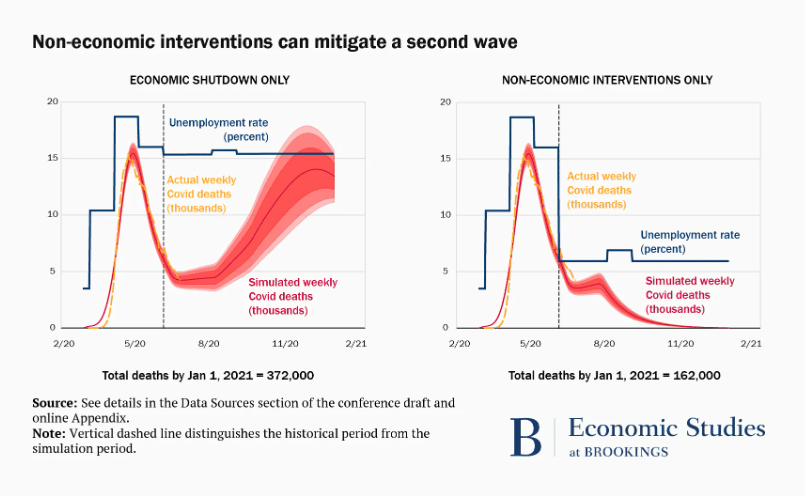

The Brookings Papers on Economic Activity mini-conference on COVID-19 happened today as a webinar. I am reading several of the paper drafts that were discussed (but did not have the chance to tune in to the webinar). I may write more here about these papers, but for now I want to emphasize this graph from the paper by Baqaee et al., Policies for a Second Wave:

The graph is self-contained, so I don’t feel the need to explain it more.

I may indeed post again, in more detail, about this and other papers presented in this conference.

Reaction to Katharina Pistor’s book “The Code of Capital”

I recently read this book and decided that I will include it in the syllabus of my Economic Inequality course. A few days ago, when I indicated on Twitter my intention to write about the book in this blog, I was intending a review. However, I found good reviews online, to which my own review would have little to add. These are: a post in the Law and Political Economy blog by Sam Moyn, and this piece by Rex Nutting on MarketWatch. To these, I can add little of value from the point of view of a legal scholar, such as Sam Moyn, or a commentator on political economy, such as Rex Nutting. Instead, I will quote from the publisher’s online blurb, so you can get a quick idea what the book is about, before proceeding with my comments.

Capital is the defining feature of modern economies, yet most people have no idea where it actually comes from. What is it, exactly, that transforms mere wealth into an asset that automatically creates more wealth? The Code of Capital explains how capital is created behind closed doors in the offices of private attorneys, and why this little-known fact is one of the biggest reasons for the widening wealth gap between the holders of capital and everybody else.

In this revealing book, Katharina Pistor argues that the law selectively “codes” certain assets, endowing them with the capacity to protect and produce private wealth. With the right legal coding, any object, claim, or idea can be turned into capital—and lawyers are the keepers of the code. Pistor describes how they pick and choose among different legal systems and legal devices for the ones that best serve their clients’ needs, and how techniques that were first perfected centuries ago to code landholdings as capital are being used today to code stocks, bonds, ideas, and even expectations—assets that exist only in law.

I am intrigued by this book, in my capacity as an economist, for two main reasons.

- The book gives a new and insightful perspective on the nature of capital, not long after Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, a book most certainly discussed in my course on economic inequality. One big criticism of Piketty’s concept of capital, leveled by other economists, is that it diverges from the standard use of “capital” in macroeconomic / growth theory, even though Piketty does appeal to some results from this theory in his analysis. Pistor offers in her book an intriguing definition of capital as the aggregation of a myriad strategies of highly-paid lawyers, who shop around existing legal systems to create encodings of assets into concepts that can be defended as being legal in some court of a recognized state, encodings that serve to make up assets out of “thin air” and make these assets long-lived, accumulating over time, and convertible to money when their owners desire. I am not a macroeconomist, but I am eager to see what my colleagues in that field will come up with by engaging with this definition. After all, Paul Romer’s 2018 Nobel prize was for his incorporation of ideas into growth theory, as boosting the productivity of all other inputs to production (yes, I am simplifying). Intellectual protection legal regimes matter for this for obvious reasons. Pistor essentially says that the ideas of lawyers are part of this process. She explicitly discusses how these lawyerly inventions have expanded the scope of intellectual property protection (simultaneously shrinking the public domain in the realm of ideas), but she says so much more about these lawyerly inventions that there ought to be plenty of material here for some new macroeconomic theory.

- The second reason this book intrigues me is that it suggests a diagnosis for the disease of ever-increasing inequality in incomes and wealth levels, with the attendant problems of social polarization, undermining of democratic systems and norms, and empowerment of more and more economic and political oligarchy. It is not the job of a law professor like Pistor to suggest to economists interested in political economy and mechanism design how to think about modeling a way forward to formulate effective social and policy responses to these trends. But she has done all such economists (and I do count myself as part of this group) a favor by her diagnosis. I hope the policy designs and suggestions from economists are not long in coming.

Long absence from this blog ends now with a post about how experiencing income inequality when growing up affects one’s preferences for income redistribution policies

The Fall semester has proved to be busier than I thought it would be. However, I really do want to come back to this blog, and a paper about inequality I encountered today gave me the push I needed.

The paper is Experienced inequality and preferences for redistribution by Cristopher Roth and Johannes Wohlfart, Journal of Public Economics 167 (2018) 251-262.

The authors use large national datasets to examine the following question: if someone experienced higher inequality when growing up, will they be more or less in favor of redistribution?

Their answer surprised me. Quoting from the abstract of the paper:

people who have experienced higher inequality during their lives are less in favor of redistribution, after controlling for income, demo- graphics, unemployment experiences and current macroeconomic conditions. They are also less likely to support left-wing parties and to consider the prevailing distribution of incomes to be unfair. We provide evidence that these findings do not operate through extrapolation from own circumstances, perceived relative income or trust in the political system, but seem to operate through the respondents’ fairness views.

(Roth and Wohlfart 2018, abstract)

People who grew up experiencing higher inequality demand less redistribution? Of course that is fine if you think of those in the top of the distribution, but the way inequality has developed in a skewed manner in most countries, the majority of the people should be in a less advantageous position and might be expected to have a desire for redistribution policy to reduce the inequality. But they don’t! The authors offer this potential explanation:

One plausible interpretation of these findings is that growing up under an unequal income distribution alters people’s perception of what is a fair division of resources, and thereby reduces their demand for redistribution.

(Roth and Wohlfart 2018, Page 252)

This is like thinking of slaves becoming used to the chains and eventually fond of them. I want to absorb the message of this paper more deeply, at least for my forthcoming class on economic inequality in the Spring 2019 semester, and if I have further thoughts to share on this blog, I will do so.

Fascinating new book by Posner and Weyl

Want to create a more just society? Reform private property radically and change how we vote. This is the message of a new book that came out this month.

Eric Posner and Glen Weyl recently published Radical Markets: Uprooting Capitalism and Democracy for a Just Society, Princeton University Press, 2018. You can get a taste of what’s in the book by the authors’ May 1st piece in the New York Times. The Economist called the book “arresting if eccentric manifesto for rebooting liberalism” in a mainly positive review.

The average person who has taken at least one introductory economics course might well be bewildered by the main economic idea in this book. It posits that private property of assets is a deep-seated, powerful source of monopoly power that undermines competition in economic markets. So reform private property, they argue. How? Didn’t we learn in school that without well-defined and well-enforced property rights perfect competition cannot take root?

The idea is not to abolish private property, however. It is to reform it drastically. Each person would publicly state the value of every asset they own. They would then be taxed on this. A wealth tax, you say, big deal, nothing new. What’s to prevent one from undervaluing their holdings to lessen their tax burden? The other part of this tax proposal, that’s what. Once you have declared a value for each of your assets, you must be willing to sell it for that amount to anyone willing to pay it. Technology, perhaps in the form of a smartphone app, would take care of the technicalities; something like Uber for trading houses.

The proceeds from this wealth tax can be used for public projects, perhaps funding a universal basic income, while the tax system would allow the efficient allocation of assets. So far, so Henry George in a modern guise. (And I learned from this book something really new to me: that no less a well-regarded economist than Léon Walras had ideas similar to those of Henry George on taxing land.)

But that’s not all! Posner and Weyl also want to bring into the voting system ideas from the economics of mechanism design. In fact, I only bought the book after I read a short article by Weyl with Steven Lalley on this in the American Economic Review’s Papers and Proceedings for 2018 (an ungated version is here).

Imagine every citizen being given a budget of “vote-buying money”, just as much as every other citizen. They would then be able to spend some of this “money” to buy extra votes for elections that concern issues they care a lot, at the cost of having fewer votes to cast in other elections. The prices of votes wouldn’t be linear, but quadratic. That is, one vote would cost one vote “dollar”, two votes would cost four, three would cost nine, and so on.

Incredibly at first thought, a voting system like this market-inspired one has nice properties in theory. Markets in everything, indeed!

It is natural for this proposal to raise concerns about individual rights, as the review in The Economist points out. However, a radical proposal may well be what we need in our time of political polarization and economic strain for more and more people. I will happily read this book to the end and prepare something to say about it in my economic inequality course. You will probably hear from me about it again in this very website.

On teaching the economics of inequality

In the Spring semester of 2017 I taught an undergraduate course on economic inequality for the first time. Every time I mention this to anyone, they want to know what I put in it. Now that I have a reasonable idea of what worked and what did not in the first outing of this course, I want to share here the basic structure of the course and some of the most important readings in it. To start with, here are the main topics, each with a short explanation and some reading suggestions. I regretted that there was no textbook for this course that presented the material I wanted to teach in the way I wanted to teach it; I have now embarked on writing such a book. (There does exist a huge Oxford Handbook of Economic Inequality, but it is not usable as a textbook, because it emphasizes breadth over depth of coverage and ends up with very brief discussions of difficult topics, that the reader has to work hard to assimilate by reading detailed expositions in the references.)

Course structure, including the main readings

- Normative reasons to care about economic inequality. You would think that why an economics student should care about inequality should be obvious to them, but I encountered, before I started the class, the question of why we should care. So I came up with this topic and the next. It didn’t hurt that I have long considered economists, in the main, much too narrow-minded regarding how to evaluate economic allocations from a normative point of view. The superb online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy has an excellent article on distributive justice, with links to other articles on related topics. The Stanford Encyclopedia’s distributive justice article is a good core reading for this section of the course. The main temptation I had to stay away from when teaching this material was to include a serious survey of the voluminous work of the Nobel laureate economist Amartya K. Sen. This work deserves an entire semester for itself. Rather than extract some bits from it without all the context, I minimized references to it, with regret. For the interested reader, the following books by Sen contain a good presentation of his pathbreaking work:

Collective Choice and Social Welfare: An Expanded Edition, 2017;

The Idea of Justice, 2009;

Inequality Reexamined, 1995;

Choice, Welfare and Measurement, 1999.

There are more books and articles by Sen and his intellectual interlocutors that arguably belong to this list, but as the list is already too long, I am leaving it as is. - Positive economic reasons to care about economic inequality. “Positive” here refers to “positive economics”, the study of “what is” in the economic sphere. In this usage, “positive” is contrasted with “normative”, the study of what ought to be, which was covered in the previous section with the discussion of distributive justice. This section focuses instead on a large experimental literature that makes up a large part of what is strangely called “behavioral economics”, the literature on the way individuals assess inequality in the way they evaluate economic outcomes. The main reading for this section is roughly the first half of this survey of the literature by Ernst Fehr and Klaus Schmidt. The main conclusion here is that individuals feel a lower level of satisfaction about economic conditions when there is more income inequality, all other things equal, even when they occupy a privileged position in the income distribution. This is not to say that everyone feels this way; rather, that enough people feel this way that force economists to study the topic of inequality because economic agents in the theories that economists build take account of inequality themselves in a way that affects their economic decisions.

- Equality of opportunity. When we are discussing economic opportunity, we usually find that even political conservatives mainly agree that individuals are responsible for their economic outcomes to the extent these follow from the individuals’ actions, but not from the individuals’ circumstances at birth that they have no control over (such as the individuals’ race). The intuitively clear way towards equality that this idea suggests is that if we equalize the starting point of everyone, then the inequality of economic outcomes that results from their actions is morally acceptable, as it results from their free agency. The main reading for this topic is the following difficult, but rewarding, article:

John E. Roemer and Alain Trannoy, Equality of Opportunity: Theory and Measurement, Journal of Economic Literature, 2016, 54(4), 1288‒1332.

There is plenty of opportunity to write a more accessible exposition of this topic, and it is part of my plan to do so. - Measurement of inequality. Given a set of data on the distribution of some economic variable, such as income or wealth, across people, how do we come up with a numerical scale to tell is how unequal this distribution is? Several measures have been proposed, and some, like the Gini coefficient, are popular with researchers and writers in the field. An easily digestible exposition (but with a few typos in formulas) is in chapter 6 of:

Debraj Ray, Development Economics, Princeton University Press, 1998.

This set of lecture slides is a good complement to the chapter from Ray’s book, if nothing else, because it corrects the typos.

While we are discussing measurement, I simply must also point out the following online sources of data, in many cases very well presented with interactive graphics:

World Incomes Database: http://www.wid.world/

Chartbook on Economic Inequality: http://www.chartbookofeconomicinequality.com/

Income inequality from the Our World in Data website: https://ourworldindata.org/income-inequality/

Clearly a data-minded person could structure an entire semester’s course on the material from these three websites alone. I chose to put the material in a broader context, in which I present the data briefly and expect the students to use the data in their term papers, if they choose empirical term paper topics. - Capital and inequality. This section is inevitable, given the enormous success of Piketty’s book Capital in the Twenty-First Century. The book became a surprise best-seller in the aftermath of the “occupy” years and there are several good critical discussions in the literature, including this excellent one by Lawrence Blume and Steven Durlauf:

Blume, Lawrence E. and Steven N. Durlauf, Capital in the Twenty-First Century: A Review Essay, Journal of Political Economy, 2015, vol. 123, no. 4, 749‒777. Available at https://www.ssc.wisc.edu/econ/Durlauf/includes/pdf/Blume%20Durlauf%20-%20Capital%20Review.pdf

Other good pieces in this debate include (I am trying hard to cite as few as possible):

Acemoglu, Daron and James A. Robinson, The Rise and Decline of General Laws of Capitalism, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2015, 29(1), 3‒28, available at http://economics.mit.edu/files/11348, as well as Piketty’s own rejoinder to his critics,

Piketty, Thomas, Putting Distribution Back at the Center of Economics, Journal of Economic Perspectives, volume 29, number 1, Winter 2015, pages 67‒88. - Globalization and inequality. In the aftermath of Brexit and the 2016 presidential election, I need not tell you why this is an issue of huge concern for the majority of voters in at least the UK and the US. The book by Branko Milanovic, Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization, is the central reading for this section, but one must not miss the critical discussion of this book here and the rejoinder by Milanovic and Lakner here. This debate is about Milanovic’s “elephant graph”, which became practically a meme online. This graph purports to show that the middle classes of rich societies have not kept up with income growth in Asian countries and among the rich in their own societies for a few decades now, hence the massive discontent about globalization one reads about in the press and finds reflected in election results.

- Technology and inequality. Robots are after our jobs, says practically everyone, or so it seems after only a few minutes of reading online about automation and its disruptive influence on work as traditionally understood. David Autor (yes, there is no “h” in his last name) has an accessible article that is the core reading for this section, in which he examines the impact of automation on employment and wage dispersion. The main lesson from this article is that the “middle-skill” occupations have been hit hard by automation, losing a lot of jobs, while jobs that need low or high skills have been treated well in terms of numbers of jobs by automation (but in terms of wages, only certain high-skill jobs have been treated well, but then these have been treated really, really well).

Autor, David H., Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation, Journal of Economic Perspectives, volume 29, number 3, Summer 2015, pages 3-30.

Other readings for the ambitious reader who cares deeply about this topic include

Acemoglu, Daron and David H. Autor, Skills, Tasks and Technologies, from the Handbook of Labor Economics, http://economics.mit.edu/files/11635; also

Webber, Douglas A., Are college costs worth it? How ability, major, and debt affect the returns to schooling, Economics of Education Review, 2016, volume 53, pages 296-310.

For some of the latest on robots, see

Acemoglu, Daron and Pascual Restrepo, Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets, MIT Working Paper, March 2017. - The impact of race and gender on inequality. There is a huge literature on the economics of discrimination. It is not possible to fit a detailed exposition of it in a small segment of a semester devoted to inequality. I found that the following two papers give enough of an introduction to these issues for anyone to pursue the topics further.

Lawrence Kahn, Wage Compression and the Gender Wage Gap, http://wol.iza.org/articles/wage-compression-and-gender-pay-gap/long;

Emmons, William R. and Noeth, Bryan J., “Race, Ethnicity and Wealth”, in “The Demographics of Wealth”, The Federal Reserve Bacnk of St. Louis, February 2015, https://www.stlouisfed.org/household-financial-stability/the-demographics-of-wealth. - Economic policy against inequality. This topic is certainly one that students waited for eagerly while we were slogging through the theoretical and empirical context just detailed in bullet points 1 through 8. Parts two and three of Atkinson’s book Inequality have an excellent discussion of detailed policy proposals by Atkinson, whose death in the very beginning of 2017 deprived the field that studies economic inequality of one of its founders and intellectual giants. One topic that is bruited about a lot online is universal basic income. Right near the end of the semester the following book came out, devoted to this topic exclusively. It is a good book, and I plan to incorporate it better in future versions of the course, when I will have had time to prepare accordingly.

Philippe Van Parijs and Yannick Vanderborght, Basic Income: A Radical Proposal for a Free Society and a Sane Economy, Harvard University Press, 2017.

Books used

Even though I did not use a book as a textbook, I did refer the students to chapters in the following three books (which have been mentioned above). After teaching the course once, I decided that, although I will cite Piketty’s book among these three, I will only assign readings from the other two books.

- Atkinson, Anthony, Inequality: What Can Be Done? Harvard University Press, 2015.

- Milanovic, Branko, Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization, Belknap / Harvard, 2016.

- Piketty, Thomas, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Belknap / Harvard, 2014.

The importance of inconspicuous consumption in maintaining inequalities

This essay by Elizabeth Currid-Halkett points out how Veblen’s old ideas about conspicuous consumption have evolved and are now sustaining a social abyss that separates our society along the dimensions of social stratification. Well worth reading!

Economic inequality, MLK, and Sam Bowles

I just came across this post from 2014 by Francois Badenhorst via a post by Evonomics. (I linked the original.) It is a quick profile of Sam Bowles, a well-known scholar preoccupied with the question of inequality. Just like Amartya K. Sen, I recommend Badenhorst’s post because it gives a succinct introduction to the work that Bowles has been doing.

A personal high point is where Bowles talks about his being one of the very first “mathematizers” of economics in the US. I agree completely with him that using rigorous mathematical techniques in economics promotes inttellectual honesty and productivity, provided it does not lead us to ask progressively narrower questions. Both Bowles and Sen are exemplars of asking deep, important questions about inequality and cooperation in economics, using deep mathematics to reach surprising answers.

I post this specifically today because Bowles mentions to Badenhorst an interaction with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Read the post at the first link above to learn all about it!

On having finished the book Sapiens

I have written here about reading Harari’s book Sapiens. I have finished the book since that post appeared. Now, separated from the time of finishing the book by a few days, in which I spent a lot of time reading graduate student dissertation proposals and writing lecture notes, I thought I would write down my lingering impression from the book.

This impression is bleak. The various revolutions Harari talks about left individual members of Homo Sapiens less well off than before, with the Agricultural Revolution as a prime example. Even worse were the effects of these revolutions (Cognitive, Agricultural, Industrial) on other species on planet Earth.

A secondary impression I got was one of a fundamental tension between Harari’s portrayal of history as proceeding without regard to what is good or bad, for humans or other species, and constantly talking about effects of historical changes as good or bad. I am perfectly content to read normative statements in a book on history (or economics, as a matter of fact), but I want a clearer idea of the author’s ethical convictions. Harari does not elucidate a moral philosophy, but one seems to be in the background, one that I would have liked to be made clearer.